Throughout the world, the prison population is rapidly aging. This issue is particularly prevalent in the United States, which comprises only 5% of the global population but holds 25% of its prisoners (ACLU, 2011). According to Ridgeway (2013), “Roughly 1 in 6 of the 1.5 million state and federal prison inmates is 50 or older, and their numbers are growing at seven times the rate of the total prison population” (p. 13). The increase in older prisoners is largely due to conservative legislation between the 1960s and 1990s, which was designed to be “tough on crime" (Maschi, Kwak, Ko, & Morrissey, 2012; Ridgeway, 2013). The tough on crime movement resulted in policies such as mandatory minimum sentencing, three strikes rules, truth-in-sentencing, and zero tolerance - all of which resulted in lengthier prison sentences with decreased chance of release.

One of the primary implications of the growth in aged prisoners is that many of these inmates are developing age-related impairments, such as dementia. In fact, aging prisoners may be more likely than the non-incarcerated population to develop dementia. As Ben-Moshe (2014a) succinctly states, “Prison is disabling.” In regards to dementia specifically, Belluck (2012) notes, “Prisoners appear more prone to dementia than the general population because they often have more risk factors: limited education, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, depression, substance abuse, even head injuries from fights and other violence” (para 7). Although statistics are not readily available on how many prisoners in the United States have dementia, Kingston, Le Mesurier, Yarston, Wardle, and Heath (2011) found that psychiatric disorders and cognitive impairments are unrecognized and undertreated for older adults in prisons. Furthermore, Maschi et al. (2012) reported that, based on a review of 10 published studies on incarcerated older adults with dementia, 1% to 44% of older prisoners have dementia, depending on the size of the correctional institution. This situation raises many ethical issues. One of the primary concerns is how the U.S. Prison System – and American society – should care for incarcerated people with dementia. Specifically, should people with dementia be cared for in prison? If so, what should this care look like? If not, should they be released and cared for in community contexts? This blogpost attempts to begin to answer these questions, with the hope of starting a dialogue about this important, although often overlooked, ethical and social issue.

One of the primary implications of the growth in aged prisoners is that many of these inmates are developing age-related impairments, such as dementia. In fact, aging prisoners may be more likely than the non-incarcerated population to develop dementia. As Ben-Moshe (2014a) succinctly states, “Prison is disabling.” In regards to dementia specifically, Belluck (2012) notes, “Prisoners appear more prone to dementia than the general population because they often have more risk factors: limited education, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, depression, substance abuse, even head injuries from fights and other violence” (para 7). Although statistics are not readily available on how many prisoners in the United States have dementia, Kingston, Le Mesurier, Yarston, Wardle, and Heath (2011) found that psychiatric disorders and cognitive impairments are unrecognized and undertreated for older adults in prisons. Furthermore, Maschi et al. (2012) reported that, based on a review of 10 published studies on incarcerated older adults with dementia, 1% to 44% of older prisoners have dementia, depending on the size of the correctional institution. This situation raises many ethical issues. One of the primary concerns is how the U.S. Prison System – and American society – should care for incarcerated people with dementia. Specifically, should people with dementia be cared for in prison? If so, what should this care look like? If not, should they be released and cared for in community contexts? This blogpost attempts to begin to answer these questions, with the hope of starting a dialogue about this important, although often overlooked, ethical and social issue.

My Approach to these Questions

Numerous scholars and social justice groups have highlighted that the U.S. Prison System is a racist, classist, ableist system that disproportionately criminalizes and imprisons people who are low-income, and/or disabled, and/or from marginalized racial communities (Alexander, 2012; Erevelles, 2014; Ware, Ruzsa, & Dias, 2014). Furthermore, the U.S. Prison System operates within a neoliberal, capitalist framework, which influences how we think about and discuss the future of imprisonment. As Ben-Moshe (2014b) writes, "Our current moment is also one of intense neoliberal policies resulting in fiscal constraints, austerity measures and privatization of social services, which simultaneously constrains and holds possibilities for the closure of prisons and large state institutions" (p. 268). I have kept these factors in mind while thinking through how we as a society should respond to incarcerated people with dementia. While I sometimes refer to numbers (economically and demographically), I believe that we need to pay attention to this issue because incarcerated people and people with dementia are ultimately human beings.

The Ethical Principle of Justice

An ethical principle that is particularly relevant when considering incarcerated older adults with dementia is justice. In medical ethics, justice involves treating others fairly, and using fairness to distribute scarce medical resources (McCarthy, 2003). However, other forms of justice are at work in the United States criminal justice system. Although a detailed historical analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, the U.S. Prison System formerly operated using rehabilitative justice, which aims to prepare convicted "criminals" to return to society as working, contributing citizens. However, the “tough on crime” policies of the 1980s and 1990s resulted in the U.S. Prison System relying more on the philosophy of retributive justice. According to Walen (2014), retributive justice follows three principles:

- that those who commit certain kinds of wrongful acts, paradigmatically serious crimes, morally deserve to suffer a proportionate punishment;

- that it is intrinsically morally good...if some legitimate punisher gives them the punishment they deserve;

- that it is morally impermissible intentionally to punish the innocent or to inflict disproportionately large punishments on wrongdoers. (p. 1)

Justice in Medical Care for Incarcerated Older Adults with Dementia

Due to the increased need for health care in old age, incarcerated older adults cost much more than younger prisoners. It costs an average of $68,000 a year to imprison a person over 50 years old, which is approximately twice what it costs to imprison younger people (Ridgeway, 2013). This cost per prisoner results in a total of over $16 billion dollars of taxpayer money annually. Despite this, older adults in prison with impairments like dementia are still unlikely to receive appropriate treatment and services. One of the primary reasons for this is that prisons were not designed with the needs of aging prisoners in mind. As Baldwin and Leete (2012) observe:

Prisons are not generally equipped to deal with infirm or disabled people…existing prison health systems are experiencing difficulties with their ability to [prioritize] beds, which are primarily intended for prisoners with acute medical needs…there is also strain on staff, as corrections officers are generally trained to manage inmate behavior, not to [recognize] and attend to the symptoms of dementia. (p. 16)

Thus, the majority of prisoners with dementia are not receiving the medical services or supports they need due the U.S. Prison System’s incapacity to deal with people with chronic, long-term illnesses and disabilities.

The lack of appropriate treatment and services violates the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, as well as the principle of retributive justice, which both state that unusual, cruel, or disproportionately large punishments are inappropriate or immoral. Maschi et al. (2012) state:

The lack of appropriate treatment and services violates the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, as well as the principle of retributive justice, which both state that unusual, cruel, or disproportionately large punishments are inappropriate or immoral. Maschi et al. (2012) state:

The United States Supreme Court has held that deliberate indifference to a prisoner’s serious illness constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment (Estelle v. Gamble, 1976). The Court states in its opinion: “denial of medical care may result in pain and suffering which no one suggests would service any penological purpose.” (p. 445).

Thus, if necessary medical treatment cannot be received in prison, change must occur. Prison systems must evolve in order to meet the needs of prisoners with dementia, or prisoners with dementia must be released in order to receive care in the community.

Providing Care in Prison

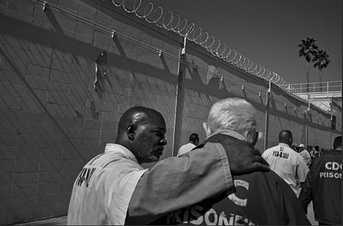

| If prisons are to provide care for people with dementia, major changes and innovative programs are required. One such program is the Gold Coats, at the California Men's Colony, which pairs aged prisoners with dementia with other prisoners who provide support and care (Belluck 2012; Hodel & Sánchez, 2012). The Gold Coats are so named because they wear distinctive gold coats in place of the standard prison uniform. The types of support and care the Gold Coats provide include: showering, shaving, eating, toileting, and changing adult diapers. They also protect the prisoners with dementia and ensure that other inmates do not bully, abuse, or victimize them. The program has been somewhat controversial because many of the Gold Coats have been convicted of murder or similarly violent offenses. However, the Gold Coats are providing assistance that the prison could not otherwise provide, and many of the Gold Coats report finding great meaning in their work. They were trained by the Alzheimer's Association and given a thick manual on dementia. As a result, the Gold Coats know more about dementia than the prison staff, and are thus better able to meet the unique needs of their fellow prisoners with dementia. | |

Maschi et al. (2012) highlight other models of dementia care in prisons. For example, in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, there is a hospice program that uses other prisoners as hospice volunteers. This program was covered in the documentary, Serving Life. The trailer for this film is below, or can be accessed here. (Unfortunately, the trailer is not close captioned.)

The “True Grit” program in the Nevada Department of Corrections includes physical activity, therapy, the arts, and other activities and has been shown to decrease the number of doctor visits and medications taken by older inmates. The Unit for the Cognitively Impaired in New York is a 30-bed unit in the prison’s medical center. It is known for having good lighting, windows, access to an outdoor patio, and common social space. Furthermore, a specially trained interdisciplinary staff consisting of psychologists, nurses, doctors, social workers, and pastors treat the patients.

In addition to these unique approaches to dementia care in prison, other changes that may be needed are structural and environmental in nature. This approach aligns with the Social Model of Disability, which promotes changing environmental and attitudinal barriers that disable people with impairments (Asch, 2001). For example, few prisons have wheelchair accessible bathrooms and showers, elevators, or bunk beds. There are also exercise and social activities that are not currently accessible for prisoners with physical or mental impairments. Many medical centers in prisons are designed to be short-term facilities, and so assisted living facilities may be necessary to care for older prisoners with chronic impairments like dementia. Lastly, correctional officers and other prison staff need training to understand the symptoms of dementia as well as how to care for prisoners with dementia. Many prisoners with dementia have difficulty complying with prison rules, procedures, and routines due to memory loss, confusion, and disorientation. Without an understanding of dementia, correctional officers may mistake this behavior for defiance and penalize the person with dementia. According to Baldwin and Leete (2012), “There is a risk of a vicious cycle where lack of training and staff awareness contribute to dementia in inmates not being recognized or treated, and the symptoms of dementia worsening from the methods used to obtain compliance” (p. 17). Therefore, if prisons are provide care for incarcerated people with dementia, structural and environmental changes must occur along with increased training and education for staff on how to best interact with and support people with dementia.

Providing Care in the Community

Conversely, prisoners with dementia may be released in order for them to be cared for in the community. Ben-Moshe (2014b), who is a proponent of prison abolition, discusses community living as an alternative to institutionalization and incarceration. However, many opponents of releasing people from prison (or the broader idea of prison abolition) raise the issue of public safety. Due to the theory of justice through incapacitation, people believe they are safer and less likely to be victims of crime if people convicted of crimes are imprisoned. Thus, many people argue that releasing people who have been convinced of criminal activities into the community will place innocent people at risk. However, as Ridgeway (2013) argues:

Keeping many of these older [people] locked away has little effect on public safety…[Many] older prisoners are in for nonviolent offenses such as drug possession and property crimes. What’s more, crime data shows that people are extremely unlikely to commit serious offenses once they hit 50. (p. 14).

Unfortunately, releasing incarcerated people with dementia is challenging for many reasons. Currently, fifteen states and Washington, D.C. have geriatric release programs and others have opportunities for medical release or compassionate release (Ridgeway, 2013). However, these releases are rarely granted. Many prisoners do not know they exist, or do not understand the process for applying. The guidelines differ state to state, and some of the guidelines are subjective and contain conditions such as “whether release would minimize the severity of the offense” (Nuwer, 2014, para 13). Furthermore, they require a significant amount of paperwork and time to process. Often, many inmates who start the application process for geriatric or compassionate release die waiting. Nuwer (2014) notes, “The…problem with compassionate release is…infirm inmates who do or should qualify for release are unjustly kept in prison, rather than being turned over to their families to care for them in their final days” (para 15). Thus, if the U.S. Prison System does decide to release prisoners with dementia so that they can receive care in the community, serious reforms are needed to ensure prisoners with dementia can be released in a timely manner.

Yet another issue related to the release of prisoners with dementia is the type of care they receive in the community. Due to their impairment, prisoners with dementia cannot be released without a plan for their care in place. “Simply pushing them out the prison door will be tantamount to a death sentence” (Ridgeway, 2013, p. 14). In some cases, families may be well equipped to provide care for a person with dementia. However, other prisoners with dementia may be from families that are no longer present in their lives, or may not have the resources to care for them. For example, in the case of one of the prisoners with dementia at the California Men’s Colony who is being cared for by the Gold Coats program, prison officials asked the family if they would like to have the prisoner with dementia paroled. The family declined, with one family member stating, “To be honest, the care he’s receiving in prison, we could not match” (Belluck, 2012, para 55). Although this is an exceptional case given this prison’s innovative program, it still points to the issue that our society needs to invest more in caring for people with dementia in the community.

However, community care or nursing home care is typically still cheaper than caring for a person with dementia in prison and also places the person with dementia in an environment better suited to their needs with access to appropriately trained caregivers. Caring for a person with dementia in prison can cost over $100,000 annually (Ridgeway, 2013), while long-term care services in a nursing home cost on average $78,110 annually (Alzheimer’s Association, 2014). Community supports, such as home health aides, personal care assistants, and adult day care services, are even more affordable and also allow the person with dementia to continue living in a community. Thus, the State may be able to provide better care for the person with dementia and still save money by partially or fully financing community care or nursing home care in certain cases, such as when there is no family involved in the prisoner with dementia’s life, or the family cannot provide care due to economic restraints.

It is important to note that it is rare in Disability Studies to advocate for nursing home placement for people with disabilities. However, I am arguing that, in this specific case, nursing home placement would be better than prison. Community living would still be ideal, but supports for people with dementia to live in community settings would need to be in place.

For instance, my favorite option for community living currently is to expand the concept of dementia villages. Dementia villages are designed to provide care and support for people with dementia in community settings, without placing them in locked wards of institutions like nursing homes. As a result, people with dementia can still experience privacy and autonomy. Furthermore, these villages have facilities (e.g., bars, restaurants, theatre) that can be used by people in neighboring communities, which means that people with dementia in these villages are not segregated from society. Ben-Moshe (2014b) highlights villages in Norway for people with disabilities that are similar to dementia villages as a way to avoid institutionalization/incarceration, and so dementia villages would be a viable (albeit presently expensive) solution.

Yet another issue related to the release of prisoners with dementia is the type of care they receive in the community. Due to their impairment, prisoners with dementia cannot be released without a plan for their care in place. “Simply pushing them out the prison door will be tantamount to a death sentence” (Ridgeway, 2013, p. 14). In some cases, families may be well equipped to provide care for a person with dementia. However, other prisoners with dementia may be from families that are no longer present in their lives, or may not have the resources to care for them. For example, in the case of one of the prisoners with dementia at the California Men’s Colony who is being cared for by the Gold Coats program, prison officials asked the family if they would like to have the prisoner with dementia paroled. The family declined, with one family member stating, “To be honest, the care he’s receiving in prison, we could not match” (Belluck, 2012, para 55). Although this is an exceptional case given this prison’s innovative program, it still points to the issue that our society needs to invest more in caring for people with dementia in the community.

However, community care or nursing home care is typically still cheaper than caring for a person with dementia in prison and also places the person with dementia in an environment better suited to their needs with access to appropriately trained caregivers. Caring for a person with dementia in prison can cost over $100,000 annually (Ridgeway, 2013), while long-term care services in a nursing home cost on average $78,110 annually (Alzheimer’s Association, 2014). Community supports, such as home health aides, personal care assistants, and adult day care services, are even more affordable and also allow the person with dementia to continue living in a community. Thus, the State may be able to provide better care for the person with dementia and still save money by partially or fully financing community care or nursing home care in certain cases, such as when there is no family involved in the prisoner with dementia’s life, or the family cannot provide care due to economic restraints.

It is important to note that it is rare in Disability Studies to advocate for nursing home placement for people with disabilities. However, I am arguing that, in this specific case, nursing home placement would be better than prison. Community living would still be ideal, but supports for people with dementia to live in community settings would need to be in place.

For instance, my favorite option for community living currently is to expand the concept of dementia villages. Dementia villages are designed to provide care and support for people with dementia in community settings, without placing them in locked wards of institutions like nursing homes. As a result, people with dementia can still experience privacy and autonomy. Furthermore, these villages have facilities (e.g., bars, restaurants, theatre) that can be used by people in neighboring communities, which means that people with dementia in these villages are not segregated from society. Ben-Moshe (2014b) highlights villages in Norway for people with disabilities that are similar to dementia villages as a way to avoid institutionalization/incarceration, and so dementia villages would be a viable (albeit presently expensive) solution.

Conclusion

The “looming problem” of growing numbers of incarcerated people with dementia is challenging and complex (Moll, 2013). Regardless of one’s personal opinion on how to best care for prisoners with dementia, it is clear that the problem cannot be ignored – changes will be required for the U.S. Prison System, as well as other prison systems around the world, to support the increasing needs of this burgeoning subset of the prison population. This paper explored two potential solutions: changing prison systems to meet the needs of prisoners with dementia or releasing prisoners with dementia in order for them to receive care in the community. However, it may be best if a combination of both solutions is instituted given the intricacy of this particular social and ethical issue. It is important for our society to collectively consider how to best address the needs of people who are incarcerated with dementia.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2014). Planning for care costs. Retrieved from: http://www.alz.org/care/alzheimers-dementia-common-costs.asp

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2011). Combating mass incarceration: The facts. Retrieved from: https://www.aclu.org/combating-mass-incarceration-facts-0

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2012). Releasing low-risk elderly prisoners would save billions of dollars while protecting public safety, ACLU report finds. Retrieved from: https://www.aclu.org/prisoners-rights/releasing-low-risk-elderly-prisoners-would-save-billions-dollars-while-protecting

- Asch, A. (2001). Disability, bioethics, and human rights. In G. L. Albrecht, K. D. Seelman, M. Bury (Eds.), The handbook of disabilities studies, (pp. 297-326). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Baldwin, J., & Leete, J. (2012). Behind bars: The challenge of an ageing prison population. Australian Journal of Dementia Care, 1(2), 16-19.

- Bedau, H. A., & Kelly, E. (2010). Punishment. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/punishment/

- Belluck, P. (2012, February 25). Life, with dementia. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com

- Ben-Moshe, L. (2014a). Disability, institutions, and prisons: Connecting deinstitutionalization and prison abolition. Lecture Presented at Access Living in Chicago, IL.

- Ben-Moshe, L. (2014b). Alternatives to (disability) incarceration. In L. Ben-Moshe, C. Chapman, & A. C. Carey (Eds.), Disability incarcerated (pp. 255-272). New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Fazel, S., McMillan, J., O’Donnell, I. (2002). Dementia in prison: Ethical and legal implications. Journal of Medical Ethics, 28, pp. 156-159.

- Erevelles, N. (2014). Crippin' Jim Crow: Disability, dis-location, and the school-to-prison pipeline. In L. Ben-Moshe, C. Chapman, & A. C. Carey (Eds.), Disability incarcerated (pp. 81-100). New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Hodel, B., & Sánchez, H. G. (2012). The special needs program for inmate-patients with dementia (SNPID): A psychosocial program provided in the prison system. Dementia, 12(5), 654-660.

- Kingston, P., Le Mesurier, N., Yorston, G., Wardle, S., & Heath, L. (2011). Psychiatric morbidity in older prisoners: Unrecognized and undertreated. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(8), 1354-1360.

- Maschi, T., Kwak, J., Ko, E., & Morrissey, M. B. (2012). Forget me not: Dementia in prison. The Gerontologist, 52(4), 441-451.

- McCarthy, J. (2003). Principlism or narrative ethics: Must we choose between them? Journal of Medical Humanities, 29, 65-71.

- Moll, A. (2013). Losing track of time: Dementia the aging prison population: treatment challenges and examples of good practice. Mental Health Foundation. Retrieved from: http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/content/assets/PDF/publications/losing-track-of-time-2013.pdf?view=Standard

- Ridgeway, J. (2013, January/Februrary). Age in the cage: Three strikes, you’re old. Mother Jones, pp. 13-14.

- Ware, S., Ruza, J., & Dias, G. (2014). It can't be fixed because it's not broken: Racism and disability in the prison industrial complex. In L. Ben-Moshe, C. Chapman, & A. C. Carey (Eds.), Disability incarcerated (pp. 163-184). New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Whalen, A. (2014). Retributive justice. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/justice-retributive/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed